Not just a pretty bird, an ugly invader

The European Starling invades North America:

We as a species have always tried to do the right thing, or at least what we think to be the right thing. We have altered the Earth in so many ways that it is doubtful it will ever return to its original state. We have moved mountains, filled in the seas, killed off huge populations of animals, and dumped our pollutants wherever we felt like it. And in our efforts to do the right thing, we have, either by good intentions or simply by accident, introduced a whole slew of creatures that have hurt our environment.

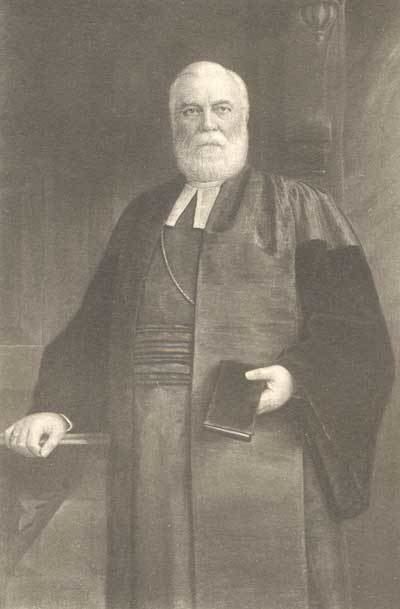

Eugene Schieffelin (January 29, 1827 – August 15, 1906)

And so it was with Eugene Schieffelin, who in 1890, decided that it might be a good idea to release 60 European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) into New York City’s Central Park. A year later he would release another batch of 40 starlings into the park. Born January 29, 1827, Schieffelin was an American amateur ornithologist who belonged to the New York Genealogical and Biographical Society and the New York Zoological Society. He was also a big fan of William Shakespeare’s writings and planned to introduce into North America all the birds mentioned in the Bard of Avon’s works.

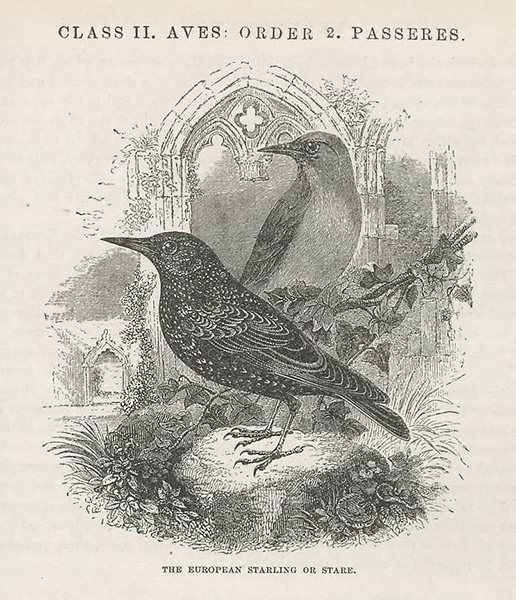

(European Starling hand-colored lithograph by John Gould and HC Richter from Gould, Birds of Great Britain, 1873, Brooklyn Museum)

Schieffelin was born in New York City, the seventh son of Henry Hamilton Schieffelin and Maria Theresa Bradhurst. His father was a prominent lawyer, who was named in honor of Governor Henry Hamilton for whom his grandfather Jacob Schieffelin had served as secretary during the American Revolutionary War. The Schieffelin family was one of the oldest families in Manhattan.

Schieffelin, a pharmacist, was the chairman of the American Acclimatization Society, which had the charter to introduce native plants and animals from Europe into North America. As a group, they brought in many species, “birds which were useful to the farmer and contributed to the beauty of the groves and fields.” The society would go global, particularly in countries that had been colonized by invading Europeans. In the 19th century, such acclimatization societies were fashionable and were supported by the scientific knowledge and beliefs of that era, as the effect that non-native species could have on the local ecosystem was not yet known.

Along with the release of European starlings, Japanese finches, and pheasants into North America, the group introduced Java sparrows, house sparrows, chaffinches, blackbirds, skylarks, and European robins.

(European Starling or Common Starling from Samuel Goodrich, Illustrated Natural History of the Animal Kingdom, 1859, Linda Hall Library)

The European Starlings thrived, and by the early 21st century, more than 200 million of them had spread throughout the United States, Mexico, and Canada. Their aggressive competition for nesting cavities has long been thought to be responsible for the collapse of several native bird populations. Starlings have also played a key role in the damage to agriculture and have been included in the IUCN List of the world’s 100 worst invasive species.

Starlings have taken over many trees and nesting sites long used by native species and this unruly starling remains today as a species that has a love/hate relationship with humans. They are a spectacularly beautiful bird who, through no fault of their own, has adapted well into its introduced environment. Their startling numbers have also been blamed for helping to spread invasive plants like English Ivy, and their impressive flock “murmurations” have disrupted air traffic.

The European Starling is considered to be one of the most publicly reviled of North America’s invasive species. But can the blame be put on this amazing creature? No, it cannot, as it was not the bird’s intention or ability to ever cross the mighty Atlantic and colonize the New World. It was the unwitting Eugene Schieffelin and the American Acclimatization Society who share the blame.

In a 2007 article in the San Francisco Chronicle, scorning the invasive introduction of fallow deer, which had been purchased from the San Francisco Zoo by Dr. Millard Ottinger for his private ranch at Point Reyes, the newspaper called the American Acclimatization Society “the canonic cautionary tale of biological pollution.”

Eugene Schieffelin died at the Hartshorn villa in Newport, Rhode Island on August 15, 1906, never fully realizing the negative impact he made to the North American ecology by his introduction of the European Starling.

(Editors note: Eugene Schieffelin was married to Catherine Tonnelé Hall, a daughter of Valentine Gill Hall Sr., an Irish immigrant, and Susan (née Tonnelé) Hall. Catherine was the sister of Valentine Gill Hall Jr., a banker and merchant who was the grandfather of Eleanor Roosevelt.)

All photographs are the copyright of Jim Jackson Photography and Nida Jackson Photography. Please contact me with any questions, comments, or for authorization to use photos or for signed, high-resolution prints.

If you found this article useful, please like, share, and follow.